Generative AI in Production

People without dirty hands are wrong.

Cult of Done Manifesto

I haven’t been lucky enough to build any Generative AI products other than playing around on my own time. I was keen to learn from those who have built these and deployed them to customers, so I attended the LLMs in Production conference back in April. This blog is a summary of what I learned, mostly from the viewpoint of someone working at a company that is well versed in ML but is feeling pressure to “do something with Generative AI”.

One thing to keep in mind there are many biases in the views given in topics like these, pessimistic ones from those fearful of change, optimistic ones from those selling picks and shovels in a gold rush, and overoptimistic ones from the future-gazers that come out in every hype cycle. I liked this conference as it seemed to balance these viewpoints well, and it was pretty clear which persona the speakers fell into (and thankfully very few of the overoptimistic ones).

Intro

LLMs are the most successful type of model commonly known as a foundation models, trained to be able to predict what the next word in a sentence would be. The major differentiator of these models is their architecture allows them to be trained on HUGE amounts of data, basically the entire internet. In learning how to do this simple task (and particularly with the addition of instruction fine-tuning), researchers discovered these models could reason, solve problems, and create new, creative-seeming pieces of work. These instruction-tuned foundation models were branded with the label Generative AI, most commonly seen with ChatGPT, DALL-E and Copilot.

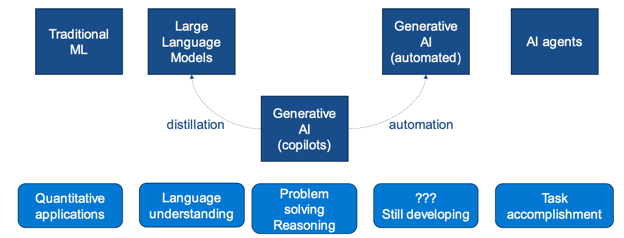

Putting this in context, we have the broad base of traditional ML that will likely still be required for quantitative, low-latency, or interpretable use cases. The public will have had the most interaction with copilot-type (i.e. a chat based interface) Generative AI, however it’s likely that the short-term successes for many non-data-rich companies will come from using these foundation models for very targeted applications (e.g. summarise this document, what is this user’s need etc.) which, as we’ll see later, can be easily tackled by distilled versions.

Beyond copilots, full automation of these models is still being worked on, and the long term future is to develop agents, capable of achieving a task e.g. ”go buy me a blue couch for my living room for less than $1000”

ML Product Development

The main benefit of LLMs that kept being brought up at the conference was the ability to reach Version 1 of your product much quicker.

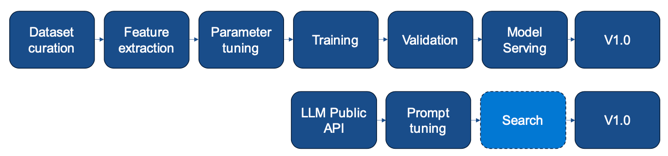

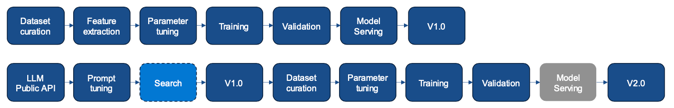

A traditional ML product has generally required the sourcing or creation of datasets, a long process of model training and evaluation, plus hosting of the model for inference. There has been a growing number of off-the-shelf solutions, but these have been for limited use cases, and so were difficult to use as differentiators for your business. Due to the zero-shot/few-shot capabilities of LLMs (and the fact they’re hosted behind a relatively inexpensive API), suddenly we have a model capable of solving a huge variety of tasks with just a bit of prompt tuning (and maybe the addition of some context). While this version of your product may be too expensive or high-latency to use at scale, it crucially allows you to evaluate product-market fit i.e. does the customer even want to use this. Too many times in the past we have gone through the traditional ML product lifecycle only to discover that the customer has no interest in the product!

What does V1 look like

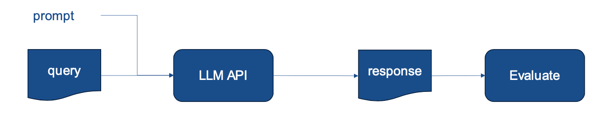

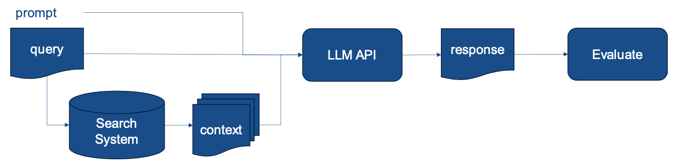

The user’s input (e.g. their query to your system) is wrapped in a prompt and sent to an LLM API (e.g. OpenAI). The response can then be parsed before sending the desired result to the user. Evaluation of the response (i.e. is this a good or bad response) allows for finding prompts that work best. Evaluation can be quite tricky for complex tasks, so you can get away with LGTM@few for V1, but the earlier you implement evaluation the better your product will be. What if the model doesn’t know anything about the task? For example, requires knowledge of data internal to your company or information from after the model was trained (e.g. the score from today’s football game). Then you want to somehow retrieve that relevant information and provide it to the model, also known as Retrieval Augmented Generation.

Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG)

It is useful to think of the model as a reasoning engine rather than a knowledge store.

This shift in thinking can help get the best out of foundation models,

as, due to their training process, they are likely to respond with any answer at all rather than say “I don’t know” i.e.s hallucinate.

Therefore, we will get more success from asking a question and providing relevant context,

which is even true of human interactions. Compare the question “What is the best bed?” to the question

“What is the best bed out of these 100 options, given that I am a 36-year-old male redecorating my daughter’s room”

Providing relevant information allows the model to respond with information not in its training data and

also helps prevent fabrication of plausible but non-existent information.

The main limitation is the quality of the search system, if you have low recall you will not be providing the

model with the facts it requires for its reasoning.

Providing relevant information allows the model to respond with information not in its training data and

also helps prevent fabrication of plausible but non-existent information.

The main limitation is the quality of the search system, if you have low recall you will not be providing the

model with the facts it requires for its reasoning.

Most descriptions of RAG assume using a vector search engine for this step, presumably because practitioners familiar with LLMs are more comfortable working with embeddings of text than using information retrieval methods. However, there’s no good reason to prefer semantic search over keyword search for this application, and generally the best choice for V1 is the search system that’s most prevalent at your company (in other words don’t spend your innovation tokens on a new search system since you likely need to spend them elsewhere in this novel product).

Beyond V1

If you get to the lucky place that V1 is actually used by customers, there are likely to be two major issues to contend with:

- Accuracy isn’t sufficient

- Cost/latency isn’t sufficient

The main solutions for these problems outlined in this great panel discussion were:

- Accuracy

- Fine tuning

- Cost/Latency

- Use in-house model

- Distill/quantize in-house model

Accuracy

There are a lot of accuracy improvements to be obtained with just the base API model. Improvements to RAG context can be obtained with better search systems. Prompt engineering (e.g. few shot prompting, chain-of-thought prompting) can make large improvements but changes to the model behind the API can render this work obsolete very quickly. At a certain point however, fine-tuning is required, particularly in domain specific applications which may not be well represented in training data for the API models e.g. legal, finance, health.

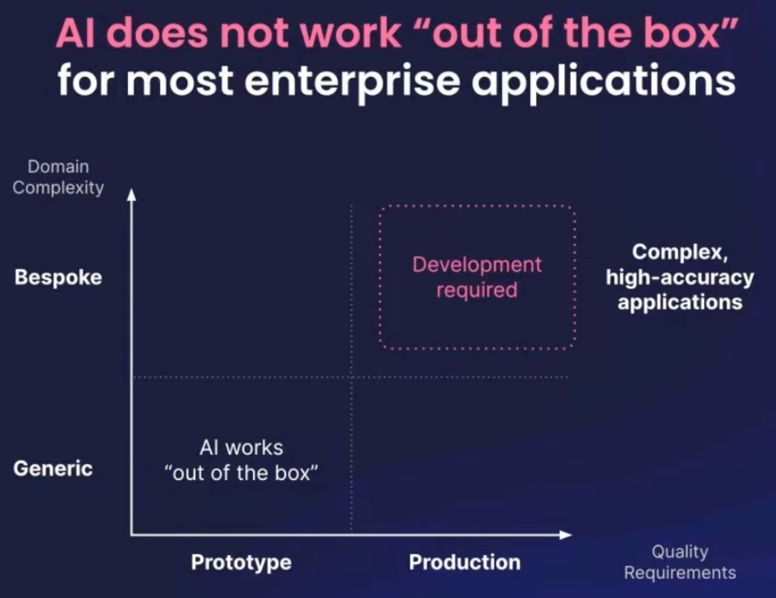

This great talk highlighted the ability for LLMs to work out-of-the-box for generic prototypes, but falling down in more complex domains. He showed 4 different use-cases in the banking, pharma, ecommerce, and legal domains with accuracies of 40-60% from off the shelf models which rose 20-30 percentage points with fine-tuning.

Fine-tuning

- Freeze most/all weights of the foundation model, fit an additional set of weights in the model

- Can be done at Open AI/GCP, but in the context of cost/latency section maybe doesn’t make sense

- Relatively cheap to finetune on these platforms so could be a good V1.1

- Numerous steps

- Labelling

- Evaluation

- Training

- Requires: Labeled examples (data) and evaluation metrics

- Nice to have: OS foundation model, self-hosting

Cost & Latency

Anecdotally, the cost and latency of OpenAI APIs are too high for production applications, particularly for high-volume automated tasks or non-chat user facing applications. High-volume automated tasks are also the tasks most suitable for training smaller expert models that can be self-hosted. An example task from this great panel discussion was summarising web pages for a web search index. The OpenAI API allowed them to evaluate whether LLMs were even capable of task, then a self-hosted, distilled open-source model allowed them to summarise every web page in their index.

In-house model hosting

- LLMs are BIG

- Naive self-hosting potentially increases the cost of latency

- Need techniques to reduce the size of model while retaining performance

Note even shrinking these models 1000x will require engineering prowess to host effectively

Quantisation

- Keep model size, reduce resolution of model weights

- For example, float32to float16 or float32 to int8

- Recently been extended to allow this to work during fine-tuning, reducing 780GB memory yo a more manageable 48GB

Distillation

- Use ”teacher” model (billion parameter) to generate training data to train “student” model (million parameter)

- Note these “small” models are still FAR larger than anything currently hosted at many companies

What does V2 and beyond look like

Using some or all of these techniques, we can reach a state where the accuracy, cost, and latency/throughput of the system is acceptable for production use cases. Note that we have re-introduced many of the steps from the ML product lifecycle we were able to leave out in the creation of V1.0, which highlights the fact that there is no free lunch in bringing ML products to production. This was a recurring theme of the conference, that current gen LLMs are excellent for generic applications and proof-of-concepts, however non-generic domains/application and production workloads are going to require a lot of custom work. The idea of simply throwing your problems to an LLM API and walking away is heavily marketed by the API providers, but the current reality doesn’t seem to bear this out.

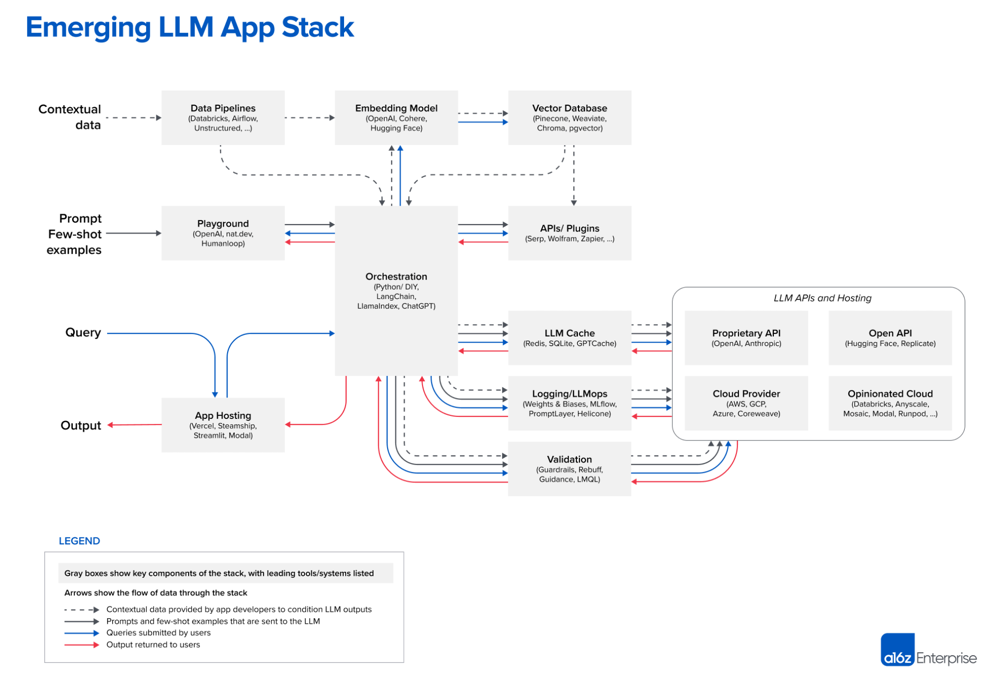

a16z (who are invested in a lot of “pick and shovel” companies, so take it with a pinch of salt) have created this architecture diagram for LLM use cases. The details aren’t important, what is most noteworthy is how little of the diagram is focused on the model, and how much is taken up by the supporting infrastructure. This is reminiscent of the infamous Figure 1 in the Hidden Technical Debt in ML Systems paper which has ML as a tiny (yet central) component in the context of the supporting infrastructure.

What Generative AI has really done is accelerated the trend of ML products moving from needing science as the lynchpin to needing engineering as the lynchpin. If your company has been investing in its MLOps capabilities, none of the above should sound worrying to you, however if they haven’t your company is at risk of falling further behind.

Next part

In part 2, we will examine some of the details of the Engineering, Science, and Data needed for succeeding with GenAI products.

- Good Science necessary but not sufficient

- Designing good evaluation

- Training and fine-tuning large models is a craft

- Mostly an Engineering problem

- This is a trend in traditional ML as seen in the recent history of MLOps

- Generative models exaggerates this due to greater capabilities and risks

- Data

- Lots to discuss!